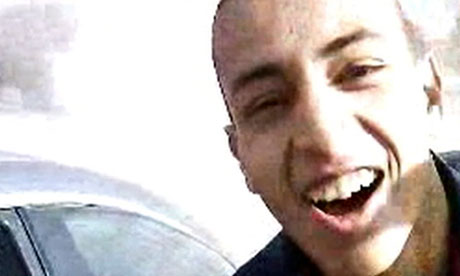

Toulouse gunman Mohamed Merah, who killed seven people including three children, sent a video of the killings to the television station al-Jazeera, it has emerged.

The Paris office of the Qatar-based broadcasters confirmed they received a letter containing a USB memory stick and a letter claiming responsibility for the murders. The memory stick was found to contain 25 minutes of video recordings of his nine-day killing spree, interspersed with what police said were "war chants".

The film was authenticated by investigators. The postal stamp on the parcel was dated last Wednesday. At the time, Merah, who expressed support for al-Qaeda, was already holed up in his flat in the south eastern city of Toulouse surrounded by police, who had swooped at 3am.

He was finally killed in a shoot-out with police on Thursday morning after a 32-hour siege.

Merah killed a rabbi teacher and three children, all under the age of ten, at a Jewish school in Toulouse on Monday 19 March. In two previous shootings he gunned down three French paratroopers, two of them Muslims, and was said to be planning further killings when he was identified and his home besieged by an elite RAID police unit.

According to police sources quoted in Le Figaro, the letter was sent from a village close to Toulouse. Detectives are now trying to establish whether Merah posted the video before returning to his flat on Tuesday, or whether he had an accomplice.

It was two weeks ago; it already seems like a century. The election campaign was beginning to send everyone to sleep. François Hollande, the Socialist candidate, was so far ahead in the polls that it was difficult to see how Nicolas Sarkozy could climb back.

It had become a campaign without excitement. Worse than that – no campaign had ever seemed so technical. The yoke of debt meant that all the candidates had their eyes fixed on figures. Five years ago, in 2007, the television coverage of the election focused on security, on schools … This time one of the broadcasting stars of the campaign was turning out to be a financial journalist, François Lenglet. This was the measure of the campaign.

But that was before the intervention in the campaign of Mohamed Merah, born like so many young Frenchmen of Algerian parents and raised on an estate in Toulouse. His father left for Algeria when he was five, his mother was largely unemployed. He left school at 16 and liked cars, especially large cars, which he drove without a licence, ending up with 18 months in prison. His journey then was one of many a small-time French delinquent from our housing estates, of Paris, Lyon, Toulouse…

Except that Merah killed – or executed, more like – seven people in a fortnight. Before dying under the bullets of Raid, the elite French police unit, he made some attempt to explain, from behind the door of the apartment that he had turned into a vast arsenal, just what had motivated his madness. The soldiers he killed in the back? Members of the 17th Regiment who had killed his "brothers" in Afghanistan. The small children from the Jewish school? A way of "avenging Palestinian children".

When this massacre took place, this strange, technocratic campaign, which seemed already written in advance, was put on hold. A truce was declared. But once Merah was in turn killed, one might have imagined that a great debate would take off, including among the candidates. And, in particular, a debate centring on this pressing question: What is Mohamed Merah the symptom of?

For the moment, at least, this is not the case. Only one question is asked, and very softly at that: have there not been serious failings and gaps in the French intelligence services? The French press asks the question, but the left hesitates to take it up. This is doubtless because the candidate of the extreme right, Marine Le Pen, has already got hold of the theme and won't let it go.

By contrast, we hear very little about what Merah says about the social malaise on our estates. And what he says about the state of affairs in our prisons, the indoctrination that takes place there, we hear nothing, or almost nothing.

The right, in power since 1995, prefers to stay silent. The left – which under François Mitterrand sinned through seeking to be angelic, preferring to celebrate a "mixed" France rather than working to anticipate the problems tied to immigration – is troubled.

Silent, on one side; troubled on the other. At least it's no longer a technocratic campaign.